5 Factories - Worker control in Venezuela

In their film Dario Azzellini and Oliver Ressler document forms of political participation in Venezuela. At the Alcasa aluminum plant in Ciudad Guayana, a textile factory in San Cristóbal, a tomato-processing plant in Altagracia de Orituco, a cocoa factory in Cumaná and a paper factory in Morón, the many layers of common ground are revealed: An uprising of suppressed knowledge (Michel Foucault) becomes visible. In a critical analysis of the state capitalism of the USSR and Cuba and social democracys employer shareholding model, worker cooperatives have searched for new forms of political activism after Hugo Chávez came to power in 1998.

Workers become the protagonists of their own story: We dont think like Commandante Chávez. Commandante Chávez thinks like we do, says a worker at the Cumaná cocoa factory. This new political culture is stimulating a production of subjectivity (Maurizio Lazzarato) at companies, which is in turn constantly challenging the political actions of advocates and representatives. As a result the workers co-administration is regarded as nothing more than a transition to their total control and self administration. In the film the strategic goals of transformation are discussed: the relations of production, an independently organized workers democracy and wage equality.

As in Venezuela von unten (2004) 5 Factories thematizes the potential of discursive resistance?a web of political knowledge and local experience which enables the attainment of knowledge of past struggles and employing this knowledge in political action.

(Ramon Reichert)

Translation: Steve Wilder

Dialogliste Deutsch

Ein Film von Dario Azzellini & Oliver Ressler

Alcasa, Ciudad Guayana (Bolívar)

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Wir befinden uns in Alcasa, Teil der Corporacion Venezolana de Guayana (CVG), eine Holding, ein Konglomerat von 16 Unternehmen, das die regionale Entwicklung unterstützt. Das Aluminiumunternehmen CVG Alcasa ist dem Ministerium für Basisindustrien und Bergbau (MIBAM) unterstellt.

Wir sind 2.700 Arbeiter bei Alcasa.

Elio Sayago, Umwelttechniker, Unternehmensleitung

Im Dezember 2004 forderte der Präsident der Republik von jedem Unternehmen der CVG ein Projekt über die Möglichkeit der Mitverwaltung in den Staatsunternehmen. Glücklicherweise gibt es ab Januar (2005) auch Änderungen im Ministerium, in der gesamten CVG. Es wird das Ministerium für Basisunternehmen und Bergbau gegründet. Minister Álvarez ernennt Carlos Lanz als Präsident des Unternehmens und es wird ein Vorstand ernannt, für den ich von Seiten der CVG ich war Arbeiter ausgesucht werde.

Die Art der Mitverwaltung, die begonnen wird in Alcasa einzuführen, bricht effektiv mit den historisch festgelegten Schemata, in dem Sinne, dass sich die Mitverwaltung historisch, sei es die deutsche, sowjetische oder kubanische, für uns immer auf Elemente der Klassenkollaboration konzentriert hat. Diese wurde durch die Sozialdemokratie geleitet, indem die Arbeiter Anteile erhielten und an der Unternehmensleitung beteiligt wurden.

Das, was wir hier in Alcasa machen, hat damit nichts zu tun. Wir haben begonnen, eine Mitverwaltung aufzubauen, die darauf beruht, die Produktionsverhältnisse zu verändern. Daher ist die Mitverwaltung für uns natürlich ein Übergangsprozess zu einer Arbeiterkontrolle oder Selbstverwaltung.

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Die neue organisatorische und politische Kultur in Alcasa besteht nicht nur aus Werten und allgemeinen Vorstellungen, sondern materialisiert sich in den organisatorischen Modellen, in den demokratischen Vorgehensweisen. Daher unterstreichen wir, seit wir hier sind, die Notwendigkeit der Veränderung der Leitungsstrukturen und es wurden neue Leiter gewählt, ausgehend von der Vision, die Entscheidungen auf einer breiteren Basis zu fällen, im Team zu arbeiten. Es wurden Triumvirate gewählt, drei Abteilungsleiter statt einem, mit Übergangscharakter, abwählbar und der Kontrolle von unten unterworfen. Aber es blieb nicht bei der Wahl der Leiter. Wir haben auch 300 Sprecher gewählt. Sie sind ein Bindeglied zwischen der Arbeiterversammlung, den Komitees und der Leitung. Diese 300 Sprecher sind also, wie es der Name sagt, diejenigen, die Vorschläge vorstellen, befragen, erforschen und gemeinsam mit dem Kollektiv, in Form von Teamarbeit, entscheiden, welche Politiken vorangebracht werden, welcher Art auch immer: Umwelt, Technologie, Forderungen, Kultur.

Dank unserer Verfassung haben wir eine Öffnung zu einem anderen demokratischen Sozialismus, mit einer Arbeiterdemokratie, in der gewählt, delegiert, Bericht erstattet und abgewählt wird. Und wir haben dieses andere Paradigma der partizipativen und protagonistischen Demokratie.

Leslie E. Turmero, Leitungstriumvirat Walzabteilung

Im Rahmen des Mitverwaltungsprozesses, der in Alcasa eingeleitet wird, waren wir das erste Triumvirat, das am 23. März diesen Jahres von etwa 260 Arbeitern gewählt wurde.

Nach den Wahlen haben wir alle Arbeiter dazu aufgerufen, an einer Erhebung teilzunehmen, die die Situation des gesamten Werkes analysiert und sich direkt an der Lösung der vorhandenen Probleme zu beteiligen. Seitdem arbeitet die Leitung mit offenen Türen. Alle Arbeiter sind an den Entscheidungen beteiligt, sie werden alle gemeinsam getroffen.

Wenn wir in andere Unternehmen kommen, uns vorstellen und der Präsident sagt: Wenden sie sich nicht an mich, wenden sie sich an die neuen Leiter, dann ist das für die Leute ein großer Schock. Alle Veränderungen führen zu einer heftigen Reaktion. Bisher war es immer eine Pyramidenstruktur mit einer einzigen Person in der Leitung.

Viele waren zunächst sehr skeptisch. Jetzt sind wir seit vier Monaten dabei und haben vier Produktionsrekorde aufgestellt mit unserer Leitung. Nun sagen sie, das ist gar nicht so schlecht.

Gonzalo Maestre, Sprecher und Supervisor der Stabgussabteilung III

Zumindest im Arbeitsumfeld führen wir ziemliche Verbesserungen durch, wir haben jetzt den Gebrauch von Chlor reduziert. Wir benutzen weniger Chlor, wir haben Maschinen mit besserer Technologie und es werden neue Maschinen gekauft wie Kühltürme, um unsere Produktion zu verbessern. Wir werden neue Gießanlagen aufbauen mit besserer Technologie, moderner, um auf dem Markt besser konkurrieren zu können. Wir sehen, dass es besser wird. Wir haben die Möglichkeit der Bildung für die Arbeiter. Einige holen ihre Mittelschule nach, andere besuchen die Ingenieursschule oder höhere technische Schule, und wir schaffen Übereinstimmung unter den Arbeitern für Verbesserungen an sich.

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Es ist ein demokratischer Prozess, der darauf ausgerichtet ist, der hierarchischen Struktur von Chefs, Vorarbeitern und Arbeitern das Rückgrat zu brechen.

Die Bilanz ist, dass hier eine neue politische Kultur aufgebaut wird. Wir konkretisieren die Verfassung in punkto Partizipation der Arbeiter, mit teilweise obsoleter Technologie, mit einem Umweltdefizit, mit organisatorischen und bürokratischen Problemen. Aber die politische Sache überwiegt, die Politik bestimmt, das ist unser Projekt in Alcasa.

Ich wurde durch den Präsidenten der Republik als Direktor der CVG ernannt, der Holding-Gesellschaft. Dann wurde ich zum Vorsitzenden des Unternehmens ernannt, um die Mitverwaltung voranzubringen. Meine Aufgabe hier sind die endogene Entwicklung und die Mitverwaltung. Aber ich wurde nicht von den Arbeitern gewählt, denn das ist ein mitverwaltetes Unternehmen, in dem die neue Leitung institutionell legitimiert wurde. Ich bin weiterhin Staat, ich repräsentiere den Staat. Aber auf dem Weg zur Selbstverwaltung müssen wir auch ermöglichen, dass die Arbeiter den Aufsichtsrat wählen. Das wird als Teil der Entwicklung der Mitverwaltung auch kommen. Mitverwaltung beinhaltet auch Mitverantwortung, Mitbeteiligung und ich habe als Leiter sogar die Macht, Direktoren, die Triumvirate zu ernennen. Aber wir haben diesen legalen Rahmen demokratisch abgelehnt, um die Entwicklung der Arbeiterdemokratie zu ermöglichen.

Ich bin in gewisser Weise kein Präsident oder gewöhnlicher Leiter. Ich bin ein Revolutionär, der aus politischen und ideologischen Gründen diesem Unternehmen geliehen wurde. Ich habe sogar gesagt, ich habe keine Ahnung von Aluminium, auch wenn ich in dieser Zeit ziemlich viel über Aluminium lernen musste. Aber ich bin hier eher in einer politischen und ideologischen Funktion, der politischen, pädagogischen, erzieherischen Leitung, als der technokratischen Leitung.

Marivit Lopez, Einheit für endogene Entwicklung

Alcasa ist ein Staatsunternehmen. Was es bisher getan hat, war 80 Prozent seiner Produktion zu exportieren. Wir fördern jetzt die endogene Entwicklung des Landes und daher wollen wir die Situation umdrehen, und dafür müssen wir Unternehmen und Industrien unterstützen, die das Aluminium in unserem Land weiterverarbeiten, vor allem in den marginalisiertesten Gebieten der Region.

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Dieses Entwicklungsmodell hat auch soziale Subjekte, es hat eine Perspektive, die wir den Übergang zum Sozialismus des 21. Jahrhunderts nennen: Alcasa fördert eine Reihe neuer Unternehmen, die wir in Venezuela Unternehmen sozialer Produktion nennen, die nicht auf Bereicherung, auf Gewinn abzielen, sondern auf soziale Gleichheit, auf Gerechtigkeit, auf die Integration der Einwohner, der Bürger und Bürgerinnen.

Marivit Lopez, Einheit für endogene Entwicklung

Dann gibt es auch die Schulungen. Sie müssen verstehen, dass es nicht darum geht, dass sie die neuen Kapitalisten werden, sondern dass es Unternehmen sind, in denen der Jahresgewinn das Wichtige ist, und der muss in die Gemeinde, in der sie leben, investiert werden. Alcasa bietet auch noch eine Begleitung an, damit diese Projekte umgesetzt werden können. Wir unterstützen sie also mit politischen und technischen Schulungen.

Ein konkreter Fall eines EPS (Unternehmen sozialer Produktion), das gerade aufgebaut wird, begleitet durch Alcasa, ist der von Furepirupa und Alumifenix. Das sind Unternehmen, die Aluminium weiter verarbeiten. Furepirupa ist eine Stiftung, die sich jetzt in ein Kooperativennetzwerk verwandelt, das Kleinbusse für den öffentlichen Personenverkehr baut.

José Luis Acosta, Kleinbuskooperative Furepirupa

Als Projekt unterstützt Alcasa uns mit dem Material. Die in Kooperativen organisierten Gemeinden, insgesamt 12 Kooperativen, sind als endogener Kern für dieses Projekt organisiert. Dieser Prototyp wird im Transportsektor der Stadt Guayana zu einer besseren Entwicklung führen, und mit Kosten es ist wichtig das zu unterstreichen die 40 Prozent unter dem liegen, was ein normaler Kleinbus im Moment auf dem Markt kostet.

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Hier befinden sich historisch Arbeitslose vor den Werkstoren, Arbeitslose, die in Gewerkschaften organisiert sind, die lange Zeit mit uns gekämpft haben. Wir haben mit ihnen gekämpft und so schaffen wir jetzt ein Ausbildungszentrum. Die sind von einer Gruppe aus dem Bausektor, sie sind sehr gewalttätig, ausgeschlossene Menschen... Diese Sektoren haben wir in der Zusammenarbeit vorgezogen. Sie arbeiten saisonal auf Baustellen und sind anschließend wieder arbeitslos. Wir wollen sie also in einen Prozess der technisch-produktiven und sozio-politischen Ausbildung integrieren, einen Raum, in dem sie sich treffen können und die Konfrontation vermeiden. Denn es ist eine Gruppe, die viele Auseinandersetzungen gehabt hat, es gab schon Tote durch Schießereien. Das sind Gruppen, die von der Mafia umgeben sind. Es sind viele Gruppen. Aber die, die mit uns arbeitet, hat sich in die Arbeit des Werkes integriert und ist also Teil des EPS, des Unternehmens sozialer Produktion. Sie werden auf permanente Weise in die Arbeit integriert. Heute werden wir einen Grundstein legen, ein historisches Ereignis, dass sich das Unternehmen anders um die Arbeitslosen kümmert, sie ökonomisch, sozial und kulturell integriert.

Einige sagen, was ich machen würde, sei purer Diskurs, Ideologie, Politik. Ihr seht, dass ich deswegen angegriffen werde. Ich verteidige weiterhin, dass wir ohne eine pädagogische Aktion und Schulung nicht dahin gekommen wären, Brüder, wo wir sind.

Wir müssen eine neue Arbeiterbewegung anschieben, anders als die korrupte Bewegung der immer gleichen Gewerkschafter, die einfach Verträge aushandeln und um Arbeitsplätze schachern. Die Gewerkschaftsbürokratie muss angegriffen werden, Brüder. Wir greifen das Imperium genauso an wie die transnationalen Unternehmen, und so müssen wir auch die Schlacht um die Gewerkschaftsdemokratie kämpfen.

Hier muss eine revolutionäre Arbeiterströmung mit Klassenorientierung aufgebaut werden. Und dieses Zentrum wird auf die Schulung der Arbeiter zielen. Das ist unser Ziel. Mit revolutionärem Schritt rufe ich euch dazu auf, an diesem emanzipativen Kraftakt teilzunehmen.

Elio Sayago, Umwelttechniker, Unternehmensleitung

Unsere Gewerkschaftsführer, die anderen Genossen, müssen begreifen, dass das, was sie jetzt suchen müssen, der Protagonismus der Arbeiter ist. Wie kann das Wissen der Arbeiter wirklich die Kontrolle garantieren? Wie schaffen wir als Gewerkschaftsführer es, dass das Wissen und die Weisheit unseres Volkes über die traditionelle Forderungshaltung der Gewerkschaften hinaus reicht? Denn aktuell haben wir die historische Chance, Gesellschaft aufzubauen, unser eigenes Schicksal zu definieren.

Marivit Lopez, Einheit für endogene Entwicklung

Die Probleme, die wir in Alcasa bei der Einführung der Mitverwaltung gehabt haben, hängen mit der Schulung zusammen. Wir waren nicht darauf vorbereitet, die Kontrolle des Unternehmens zu übernehmen. Aber ich glaube dennoch, dass wir bedeutende Schritte nach vorne gemacht haben. Wir müssen vielleicht nur die Teamarbeit verstärken. Wir begannen damit, Komitees aus Teilnehmern der verschiedenen Bereiche zu bilden. Die sind zum Teil etwas abgefallen, weil sie keine klare Ausrichtung hatten. Wo gut geschulte Leute dabei waren, mit Klarheit in der Vorgehensweise, ist es vorwärts gegangen. Aber dort, wo die Arbeiter keine politische Schulung hatten oder ein Bewusstsein darüber, was wir erreichen wollen, hat die Arbeit nachgelassen. Doch aktuell schieben wir die Komitees wieder an und kanalisieren alle Zweifel dorthin, um ihnen eine Richtung zu geben und zwar auf der Grundlage von drei Achsen: Erstens, der partizipative Haushalt, zweitens, die technologische Anpassung, die das Werk braucht, um weiter zu arbeiten, drittens, die sozio-politische Schulung. Denn um die Kontrolle zu erlangen, müssen die Menschen ausgebildet sein und verstehen, warum wir die Dinge tun.

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Aber es ist eine Tatsache, dass wir uns im Kapitalismus befinden. Wie macht ein Unternehmen im Rahmen des Kapitalismus Druck in Richtung Sozialismus? Das ist die Herausforderung der venezolanischen Revolution. Wenn wir das als Übergang sehen, wo das Alte noch nicht abgestorben und das Neue noch nicht geboren wurde, dann müssen wir die neuen Produktionsverhältnisse voranbringen, stärken, begleiten.

Aber es muss globale Veränderungen geben. Ich denke, dass auch kleinere Veränderungen nicht möglich sind, wenn wir nicht die gesamten Strukturen des Staates und der Gesellschaft in Venezuela transformieren. Wir düngen jetzt den Boden. Denn wir können nicht darauf warten, alles zu verändern, um mit den Veränderungen zu beginnen. Die Dialektik zwischen Reform und Revolution haben wir hier klar.

Und wenn der Weg der bolivarianischen Revolution in Richtung Sozialismus geht, dann sind wir eines der Pionierunternehmen, das die Produktionsverhältnisse verändert, ohne, dass sie sich auf globaler Ebene verändert hätten. Der Angriff auf die gesellschaftliche Arbeitsteilung ist eine zivilisatorische Veränderung. Keine Revolution hat sich das jemals offen vorgenommen.

Elio Sayago, Umwelttechniker, Unternehmensleitung

Präsident Chávez bezog sich kürzlich darauf, dass dies eine historische Chance sei nach 500 Jahren, nach 200 Jahren. Und was wird die Garantie dafür sein, dass wir uns nicht irren? Oder dass wir nicht schon wieder eine vorübergehende Wohlstandsphase durchmachen und dann die Ausbeutung des Menschen durch den Menschen zurückkehrt? Für uns ist das mit der Frage des Bewusstseins und des Wissens verknüpft. Da muss die Information, die normalerweise eine Wissensgesellschaft im menschlichen Wesen bewegt, differenziert werden von dem, was wirklich geschieht. Wir beziehen uns immer darauf, dass man nicht vergessen sollte, dass die Menschheit unter der intellektuellen Autorität von Aristoteles etwa 1000 Jahre lang glaubte, die Erde sei eine Scheibe. Das muss man sich mal vorstellen: Tausend Jahre lang war das Potential der Entwicklung des Menschen von dieser Vorstellung konditioniert. Um eine solche Größenordnung geht es aktuell. Wir müssen das Traditionelle, den Klassenkampf mit eingeschlossen, dahin führen, in der Funktion dessen zu arbeiten, was wir aufbauen wollen. Es gibt nun eine Diskussion unter Revolutionären, ob wir den Feind angehen und ihn zerstören oder was wir denn tun sollen. Für uns geht der Aufbau über die Zerstörung. Wenn wir aufbauen, garantieren wir die Zerstörung. Und wenn wir unsere Arbeiter, unsere Bevölkerung darauf konzentrieren, neue menschliche Beziehungen aufzubauen und das ist, was für uns auf dem Spiel steht dann garantieren wir zugleich die Zerstörung des Bestehenden, die Zerstörung der Negation, die bisher für das menschliche Wachstum bestanden hat.

Kooperative Textileros del Táchira, San Cristóbal (Táchira)

Dulfo Guerrero, Koordinator Werk I

Dieses Unternehmen produzierte zu 99%, es verkaufte viel. Es wurde nicht aufgrund wirtschaftlicher Ursachen geschlossen, wegen der Funktionsweise oder aufgrund von Rohstoffmangel, nichts von alledem, sondern in Folge der Vernachlässigung durch die Besitzer. Diese trugen damals die Verantwortung, aber das Unternehmen als solches interessierte sie nicht. Sie benutzten es als Pfand, um Darlehen zu erhalten, die aber im Unternehmen nicht ankamen. Sie lenkten sie um, bis die Schulden das Unternehmenskapital weit überstiegen und unbezahlbar wurden. Dann haben sie das Unternehmen auf völlig unverantwortliche Weise geschlossen. Wir wurden alle rausgeschmissen, ohne die Zahlungen zu erhalten, die uns gesetzlich zustanden.

José del Carmen Tapias, Koordinator für Bildung und soziale Entwicklung

Textileros del Táchira ist eines der 75 venezolanischen Unternehmen, die von den Arbeitern wieder in Gang gesetzt wurden.

Nachdem dieses Unternehmen fast vier Jahre lang geschlossen war, organisierten sich die ehemaligen Beschäftigten in einer Kooperative.

Wir fühlten uns zweifellos dadurch gestärkt, dass unser Präsident Hugo Chávez Frías sagte: Organisiert euch in Kooperativen.

Die geschlossenen Unternehmen wurden auf unterschiedliche Weise zurück gewonnen, aber immer mit Beteiligung der Arbeiter. Es gibt die selbstverwalteten Kooperativen, wie unser Fall, Textileros del Táchira, die direkt durch die Arbeiter wieder in Gang gesetzt wurden, ohne eine Beteiligung des Unternehmers oder der Regierung. Von der Regierung haben wir einen Kredit erhalten, der zurück bezahlt werden muss. Aber wir sind eine Kooperative, die von den Beschäftigten, ihren legitimen Eigentümern, verwaltet, geleitet und geführt wird.

Wir kümmern uns jetzt um den Baumwollanbau, damit im Táchira genügend Baumwolle wächst, um unseren Bedarf zu decken. Und damit Arbeitsplätze im landwirtschaftlichen Sektor entstehen. Wir haben gelitten. Wir sind Opfer kapitalistischer Sektoren, die mit den Baumwollpreisen machen, was sie wollen. Daher haben wir Interesse, direkt mit den Produzenten zu verhandeln. Wir wollen mit den kapitalistischen Sektoren brechen, die immer die Wirtschaft des Landes bestimmt haben.

Luis Álvarez, Verwaltungsleiter

Um die Kooperative zu gründen, haben wir eine Gruppe aus Ingenieuren und Verwaltern gebildet, einen Arbeitsplan, ein Projekt, ausgearbeitet und dieses dann am 19. März 2005 den nationalen Institutionen vorgelegt. Nach anderthalb Jahren harter Kämpfe, Reisen nach Caracas und wichtigen Versammlungen, haben wir es geschafft, einen Kredit in Höhe von 3,4 Milliarden Bolívar zu erhalten.

Mit dem Kredit haben wir eine 40-Prozent-Phase begonnen. Aktuell verarbeiten wir 40.000 Kilo Baumwolle, alles aus nationaler Produktion, um uns nach und nach auf den Markt zu begeben und mehr Leute zu integrieren. Aktuell sind wir 118 Personen, aber wenn die Kooperative zu 100 % läuft, dann sind es 226.

Wir haben ein Jahr Gnadenfrist und dann beginnen wir den Kredit zurückzuzahlen, acht Jahre lang in dreimonatlichen Zahlungen von 176 Millionen Bolívar. Aber angesichts unserer Einnahmen planen wir, den Kredit in spätestens vier Jahren abzubezahlen, das müsste gehen.

Mittels unseres Kooperativenmodells wollen wir nicht, dass die Leute sich bereichern, aber auch nicht, dass sie weniger verdienen und ausgebeutet werden, sondern dass wir zu einer besseren Lebensqualität gelangen, dass unsere Teilhaber ein würdiges Leben haben, unsere Kinder eine würdige Bildung. Das sollen die Richtlinien unseres Wachstums sein, nach denen sich das orientieren wird, was wir oder der Präsident den Sozialismus des 21. Jahrhunderts nennen.

Rigoberto López, Koordinator der Abteilung Spinnerei

Es gibt keine Leitungsposten mehr, wir sind alle gleich. Wir hängen von einer Versammlung ab, welche die Kooperative bestimmt. Wenn immer es Zweifel gibt, wird eine Versammlung organisiert, um die Angelegenheiten zu diskutieren, und diese stimmt dann zu oder nicht. Die Versammlung ist praktisch der Chef des Unternehmens. Bei uns z. B. gibt es die Präsidentschaft, die Prüfungsstelle, die Schatzmeister, aber das sind administrative Ämter.

Als die Idee der Kooperative entstand und sie mich fragten, ob ich Teil einer zukünftigen Kooperative sein wollte, war es eine große Freude für mich. Denn ich war das ganze Leben lang, fast 43 Jahre, Textilarbeiter. Dann war ich vier Jahre arbeitslos und hatte nichts zu tun, denn ich hatte ein kleines Geschäft, das nichts hergab. Für mich ist es großartig, wieder das zu machen, was ich mein ganzes Leben lang gemacht habe, die Mechanik und die ganzen Sachen, die man in einer Abteilung handhabt. Das ist großartig, es ist, wie das Leben zurück zu gewinnen.

Carolina Chacón, Verwaltung

Ich habe 1995 in Telares del Táchira begonnen und blieb, bis das Unternehmen schloss. Über die fünf Jahre, die ich hier gearbeitet habe, kann ich mich eigentlich nicht beschweren. Es war gut, aber die Entscheidungen, die man selbst getroffen hat oder die Ideen, die man beitragen konnte, wurden nie berücksichtigt. Der Besitzer entschied einfach. Und sie haben geschlossene Versammlungen organisiert, aus denen nie Informationen zu den Arbeitern und Angestellten nach Außen drangen. Wir mussten uns darauf beschränken, Aufgaben zu erfüllen. Wie man so allgemein sagt, Schicht von 8 bis 12 und von 2 bis 6. Dann ab nach Hause und wir konnten keine Ideen beitragen. Als das Unternehmen dann schloss... Meine Mutter arbeitete seit 1976 hier, ich bin eigentlich in diesem Unternehmen geboren... Als es dann Jahre später schloss, war das sehr negativ für uns. Denn das ganze Leben dreht sich hier um Telares del Táchira. Eines Tages kam die Idee auf, die Kooperative zu bilden. Für uns war es sehr überraschend, eine Art Traum, den wir gar nicht richtig fassen konnten. Seitdem haben wir uns engagiert, wir haben gesehen, dass wir diesen Traum mit der Regierung Wirklichkeit werden lassen konnten.

Der soziale Aspekt ist sehr wichtig für die Kooperative. Er hat in uns und vor allem in mir großes Interesse geweckt.

Es gibt viele Ideen, was wir der Gemeinde anbieten können, wie Barrio Adentro, kostenlose medizinische Versorgung für die gesamte Gemeinde, für die Familien der Jungs der Kooperative. Darüber hinaus die Bildungsprogramme. Das gehört zu den wichtigsten Punkten, die wir in Angriff nehmen, Bildung und Gesundheit.

Dulfo Guerrero, Koordinator Werk I

Hier gewinnen alle. Denn es geht nicht um ein Einzelinteresse, sondern ein kollektives Interesse. Das erfüllt uns umso mehr mit Zufriedenheit. Ich denke, das ist ein Beispiel, dem es zu folgen gilt. Ich denke, das ist der Weg, um aus der Armut herauszufinden, die es im Land und in der Welt gibt. Denn auf diese Weise erhält die Bevölkerung, die nie beachtet wurde, mehr Beteiligung. Hier haben wir früher leider viel für nur eine Person produziert. Und obwohl wir viel produziert haben, waren wir weiterhin arm. Heute sind unsere Lebensumstände ganz anders. Ich würde sagen, es ist ein aufregendes Glücksgefühl.

Carmen Ortíz, Spulmaschinenarbeiterin

In der Kooperative zu arbeiten ist viel besser, als für andere zu arbeiten, denn das ist, wie ein Sklave der anderen zu sein. In der Kooperative ist das nicht so, denn jeder arbeitet auf seine Weise. Klar, das heißt nicht, dass eine in der Kooperative macht, was sie will. Man macht das, was man machen muss, ohne die Notwendigkeit, herumkommandiert zu werden.

Dulfo Guerrero, Koordinator Werk I

Der Unternehmer betrachtet den Arbeiter immer auf einschüchternde Art. Wir konnten zweifelsfrei feststellen, wie sie den Arbeitern, die hier über 30 Jahre im Dienst des Unternehmens standen, großen psychischen Schaden zugefügt haben. Heute ist das anders, das Gegenteil. Wenn uns der Produktions- oder Verkaufsleiter besuchen, verspüren wir eine große Freude. Warum? Weil wir wissen, dass es die Personen sind, die sich um die Interessen der Kooperative, das Wohlergehen aller, kümmern.

Wir fordern von denen, die die Verantwortung in der Verwaltung tragen, dass sie möglichst klar, möglichst präzise sind, und keine Informationen verbergen, damit sie keine bösen Überraschungen erleben. Denn wir sind uns völlig im Klaren darüber: Wenn die Verwaltung hier nicht den Ansprüchen der Kooperativenmitglieder genügt, dann riskiert sie, die Kooperative verlassen zu müssen.

Tomates Guárico - Caigua, Altagracia de Orituco (Guárico)

Zulay Boyer, Arbeiterin

Am 7. Juli haben wir, 58 Arbeiter, das Unternehmen besetzt. Wir 58 Arbeiter sind im Unternehmen geblieben, denn wir sind große Kämpfer für die Selbstverwaltung. Wir haben die Besetzung drei Monate lang gehalten. Das war eine Einheit unter den Arbeitern. Wir haben hier geschlafen und gegessen, ohne Unterschiede und mit unseren Kindern.

Im Jahr 2000 schloss das Unternehmen aufgrund fehlender Rohstoffe. Im Jahr 2004 wurde das Unternehmen Caigua mit einem Kredit der Regierung wieder eröffnet. Jetzt reaktivieren wir als Kooperative das Unternehmen, das aufgrund von Missmanagement erneut geschlossen wurde. Geld bekommen wir von INAPYMI (Nationales Institut für kleine und mittlere Industrie). Wir haben einen breiten sozialen Kampf geführt, damit wir selbst als Kooperative das Unternehmen reaktivieren.

Das Problem entstand, als sie dem Herrn Salomon Garcia Kredite in einer Höhe von 6.200 Milliarden Bolívar gaben und er sie in Wirklichkeit für sich persönlich ausgab, wofür dieser Herr den Kredit ja nicht bekommen hatte.

Der Herr, der Direktor des Unternehmens, Salomon Garcia, kaufte nämlich Landgüter, Grundstücke. Er hat sich eine Asphaltiermaschine gekauft für 350 Millionen, und zwar kurz, nachdem er den Kredit bekommen hatte. Das war natürlich nicht Ziel des Kredits, das Geld sollte ja in das Unternehmen investiert werden. Er erzählte Präsident Chávez, dass hier 220 direkt Beschäftigte seien und 1.500 indirekte Arbeiter, das war aber gar nicht so. Denn hier waren wir nur 60, und hier wurden Repressalien ergriffen gegen die Arbeiter.

Als dann auch der Lohn nicht mehr bezahlt wurde, hat uns das nach einem Monat dazu gebracht, die Initiative zu ergreifen. Vorher sagten wir immer, wir besetzen den Betrieb. Aber wir hatten keine solide Rechtfertigung. Als aber die Bezahlung ausblieb, haben wir uns zusammen getan und das Unternehmen besetzt. Wir haben nicht zugelassen, dass am 7. um acht Uhr morgens der Aufsichtsrat in das Unternehmen kam. Und bis zum heutigen Tag konnten sie nicht reinkommen und sie werden nicht hereinkommen. Denn hier sind wir, die Teile der revolutionären Arbeiter. Wir machen weiter mit der Revolution, damit alle Unternehmen, die besetzt oder schlecht verwaltet sind, in die Hände der Arbeiter übergehen. Denn die Unternehmer oder die, die sich Unternehmer nennen lassen, taugen nicht dazu, irgendwas in Unternehmen zu unternehmen.

Santos Pérez, Produktionskontrolle

Als wir beschlossen haben, das Unternehmen zu besetzen, war es weit unter der vorgesehenen Arbeitskapazität, vielleicht bei zehn Prozent. Ein Unternehmen, das 100 Prozent arbeiten kann, arbeitete mit 10 Prozent Kapazität.

Wir haben beschlossen, das Unternehmen zu besetzen, um es zur normalen Arbeitskapazität hochzufahren. Jetzt sind wir bezüglich der Aussaat der Tomaten dabei, den Produzenten mit den Maschinen zu helfen, sie zu unterstützen, um Tomaten auszusäen, zu produzieren und hierher zu bringen, wo wir sie in Tomatenmark verarbeiten. Aus dem Rohstoff Tomatenmark können wir Produkte abfüllen in verschiedenen Größen und Ketchup herstellen.

Wir haben Kapazitäten, um täglich mehr als 1.400 Kisten Ketchup mit jeweils 24 Einheiten zu produzieren. Dieses Produkt liefern wir den Konsumenten mittels des staatlichen Vertriebsnetzes Casa. Sie kümmern sich darum, es über die Mercal-Läden zu vertreiben. Also auf dieser Seite läuft es für uns schon einigermaßen, denn was wir produzieren, vertreibt Casa mittels des Mercal-Netzwerks. Wir blicken also nach vorne und wollen das Unternehmen auf 100 Prozent Produktion hochfahren, mit Produkten aus der Region, denn hier in der Region werden Tomaten angebaut.

Wir tun das, was wir von Anfang an geplant hatten, nämlich aus diesem Unternehmen ein Unternehmen sozialer Produktion zu machen. Ein Unternehmen, in dem nicht nur wir Arbeiter Vorzüge haben, sondern auch die Gemeinde an sich. Da bewegen wir uns hin. Ich glaube, wir werden es schaffen. Wir werden beweisen, dass wir Arbeiter in der Lage sind, das Unternehmen voranzubringen ohne die Notwendigkeit eines Besitzers.

Zulay Boyer, Arbeiterin

Wir 58 Arbeiter dieses Unternehmens haben uns in Kooperativen organisiert. Wir sind dafür in Valle de la Pascua gewesen. 15 Tage vorher hatten wir unsere Forderungen bei der Beratungsstelle des Arbeitsministeriums eingereicht. Nach einer Weile wurden wir von Leuten vom Arbeitsministerium betreut, wir haben vorübergehend einen Spezialaufsichtsrat gegründet. Dieser vertritt uns Arbeiter jetzt im Unternehmen.

Wir haben uns als Kooperative organisiert und müssen einen legalen Status erlangen. Als Kooperative organisiert, können wir einen Kredit vom Arbeitsministerium erhalten, um das Unternehmen voranzubringen.

Hier in diesem Unternehmen verdienen wir alle gleich viel, egal ob leitender Techniker oder Verwaltungsangestellter. Wir haben die gleichen Rechte.

Domingo Meléndez, Berater für Qualität, Forschung und Entwicklung

Der soziale Unterschied zwischen einem kapitalistischen Unternehmen und einem Unternehmen auf dem Weg zur gesellschaftlichen Mitverwaltung liegt in seiner Ausrichtung. Die kapitalistische Ausrichtung wird die Gewinne immer in eine persönliche Richtung lenken, ohne gesellschaftliche Vorzüge, sondern in einige Vorzüge, die nicht zum Wohl der Gesellschaft beitragen, und sich nicht in einem kulturellen, sozialen und wirtschaftlichen Fortschritt in der Welt von heute ausdrücken.

Aury Arocha, Laboranalystin

Die kapitalistischen Unternehmen arbeiten nur für sich, und wir versuchen genau das Gegenteil. Wir versuchen für die Gemeinschaft zu arbeiten, im Sinne der Gesellschaft, dass alle etwas davon haben, nicht nur die Arbeiter hier im Unternehmen, sondern auch die Leute draußen, die Bevölkerung.

Auf den Versammlungen treffen wir die Entscheidungen. Die Versammlung ist es, die jede Entscheidung trifft. Und zwar gibt es einen Prozentsatz von 50 plus ein Prozent, aber da wir total geeint sind, entscheiden wir alle und jede Meinung, von jedem einzelnen, zählt. Das ist sehr wichtig. Wir sind stark geeint und für jede Art von Entscheidung, jeden Vorschlag, jedes Projekt, bilden wir die Versammlung und beschließen, was getan wird.

Unsere Art zu arbeiten ist jetzt ganz anders. Vorher haben wir wie in einer Diktatur gearbeitet. Jetzt nicht mehr, jetzt sind wir frei. Wir sind frei, aber nicht um zu tun, was wir wollen. Wir arbeiten jetzt ganz gemeinschaftlich. Wir sind völlig spontan in unseren Ansichten und arbeiten harmonischer.

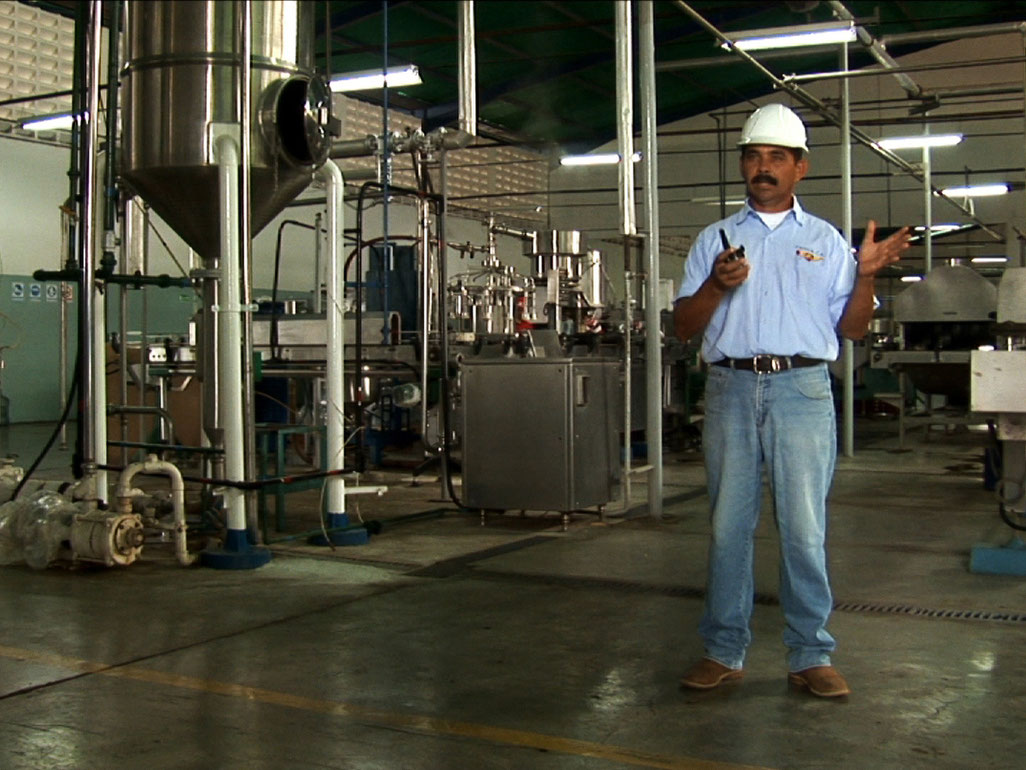

Unión Cooperativa Agroindustrial del Cacao, Cumaná (Sucre)

José Gregorio Moy, Produktionskoordinator

Wir befinden uns hier im Agroindustriellen Kakaounternehmen, ein Projekt, das auf Initiative des Gouverneurs Ramón Martinez und des Präsidenten der Republik entsteht, um dieses Unternehmen wieder in Gang zu setzen, das acht Jahre lang still stand. Das Lebensmittelunternehmen La Universal, Perugina, ging aufgrund von Fehlmanagement in die Hände der Bank über. Die Bank verkaufte es der Regierung mit einem Kredit des Ministeriums für Basisökonomie, dem MINEP. Den Kredit übernahm dann die Kooperative und sie gaben uns ein Jahr Gnadenfrist, in dem wir nichts zahlen müssen. Im Augenblick verarbeiten wir nur den Rohstoff, der von den Bauern kommt, den Kakao, und verwandeln ihn in Kakaomasse. Wir verkaufen im Moment die Kakaomasse und wollen in Zukunft Fertigprodukte herstellen, um so unseren Rohstoffen einen zusätzlichen Wert zu verleihen, also Kekse, Waffeln, Schokopralinen, Schokoladentafeln und glasierte Produkte.

Juana Ruíz, Verantwortliche für Verkauf

Wir werden durch den Staat geschützt, denn der Staat hat dem Kapitalismus und den Besitzern großer Unternehmen gesagt: Beeil dich, denn wenn du nicht produzierst, dann setze ich andere Leute zum Produzieren hin. Ich habe viele Arbeitslose und Bereitschaft und Kapital zum Handeln.

Wir sind zusammen mit den acht Produzentenkooperativen und der Verarbeitungskooperative Eigentümer des Kapitals. Wir sind Eigentümer dieser Infrastruktur, d. h. der Agroindustrial Cacao. Wir sind Eigentümer der Bohnen, der Plantagen. Wir sind auch Eigentümer der Verantwortung für mehr als 18.000 Kakaobauern im Bundesstaat Sucre, eine Antwort zu finden für 45 Prozent der Kakaoproduktion Venezuelas.

Es ist ein Nachteil, eine Schwäche, dass der Preis des venezolanischen Kakaos an den Börsen in New York und London festgelegt wird.

Ich weiß, dass es sehr schwer ist, den Sozialismus des 21. Jahrhunderts aufzubauen, aber es ist nicht unmöglich.

Wir sind viele junge Leute, die in einem Bewusstseinsprozess den Sozialismus des 21. Jahrhunderts aufbauen könnten, nein, nicht könnten, wir sind dazu verpflichtet! Und gestützt auf viele Leute, die viele Kenntnisse haben, die ihr Leben der Revolution gewidmet haben, und unermüdlich weiter geben, innerhalb und außerhalb der Regierungsstrukturen kämpfen und versuchen, den Sozialismus des 21. Jahrhunderts aufzubauen, Schläge einstecken von Rechten in der Regierung und von denen, die sie wegen ihres Diskurses lächerlich machen.

Wir sind das erste Unternehmen sozialer Produktion im Land, das erste Unternehmen, das den Rahmenvertrag mit dem Ministerium für Basisökonomie und dem venezolanischen Staat unterschreibt, Verantwortung gegenüber der venezolanischen Bevölkerung zu übernehmen. Wir sind nicht ein weiteres Unternehmen des Kapitalismus, wir sind ein Unternehmen mit Verantwortung für den Rest der Bürger, die unser Land bilden. In unserem Fall haben wir in der Nähe des Unternehmens drei Gemeinden, die mit einem Projekt sozialer Produktion von uns betreut werden. Mittels der Schaffung einer Hydrokultur-Einheit für grünes Viehfutter und verknüpft mit den diversen Kooperativenstrukturen von ländlichen Höfen wird versucht, die Ernährungskette zu vervollkommnen; was die vielen Elemente betrifft, die in der Schokolade zusammenkommen, da sind z. B. der Zucker und die Milch. Damit wollen wir Arbeitsmöglichkeiten bieten, es würden direkte Arbeitsplätze entstehen für Arbeiter und Leute aus den Gemeinden.

Es ist ein Projekt mit vielen Ambitionen, es braucht einige Zeit und Liebe den Leuten gegenüber. Denn in Wirklichkeit ist das alles, was wir tun, ein Prozess der Transformation der Köpfe, der Lebensvorstellungen. Es ist eine neue Lebensvorstellung, ein Unternehmen sozialer Produktion.

Edith Mendoza, Qualitätskoordinatorin

Wir bekommen die Kakaosäcke ins Lager, dort wird eine Probe entnommen, und diese Probe kommt hierher ins Labor, wo wir die Analysen durchführen, um die Qualität der Bohnen festzustellen. Danach kommen die Bohnen zum Rösten. Dann vom Rösten geht es zur Phase der Schälung und des Mahlens, dort erhalten wir die Kakaomasse. Bisher produzieren wir nur Kakaomasse, diese kommt dann in die Presse, wo wir die Kakaobutter von der Kakaomasse trennen.

Cacao besteht aus Uproca, das sind die Kakaoproduzenten und Chocomar. Chocomar, das sind die Arbeiter des Werks, besteht aus 96 Teilhabern und Uproca aus 3.600. Wir haben eine Versammlung aus 32 Mitgliedern, 16 von Uproca und 16 von Chocomar, wo die Entscheidungen getroffen werden, die dann der Leitung weitergegeben werden. Die Leitung besteht aus vier Genossenschaftern von Uproca, vier von Chocomar und dem Direktor. Dort werden die Vorschläge diskutiert und Entscheidungen getroffen bezüglich Cacao.

Die 16 Mitglieder werden in der Generalversammlung einer jeden Kooperative gewählt.

In Cacao Sucre wurde beschlossen, dass wir alle das gleiche Einkommen, bzw. Gesellschaftervorschuss erhalten. Wir verdienen alle gleich viel, vom Leiter zu den Arbeitern, die wir die Kooperative Chocomar bilden.

Alexander Patiño, Arbeiter

Früher war ich ein Arbeiter dieses Betriebes, als er kapitalistisch war. Das Werk war acht Jahre lang geschlossen. Im Rahmen unserer Verfassung und des revolutionären Projekts haben wir das Unternehmen zusammen mit der Regierung übernommen. Jetzt bilden wir eine Kooperative. Früher kamen wir am Montag und warteten nur auf den Lohn, auf den Freitag, wir gehörten zum Maschinenpark. Der Besitzer kam und sagte: arbeitet und es wurde gearbeitet. Stoppt und wir haben aufgehört. Jetzt ist das nicht mehr so, nun haben wir unsere Augen geöffnet, unsere Köpfe und unsere Herzen. Das Unternehmen gehört nicht nur uns, es gehört den Gemeinden. In unserer Mensa essen 40 Kinder aus der nahe gelegenen Gemeinde, die Ärmsten.

Wenn von Sozialismus die Rede ist, erschrecken viele. Was wird das sein? Sozialismus ist in wenigen Worten Liebe, Freude und soziale Gerechtigkeit. Früher hatten wir das nicht, wir wussten nicht einmal davon. Wir liefen, weil wir die anderen laufen sahen. Früher haben andere unsere Geschichte geschrieben. Seit Kolumbus angekommen ist, wurde die Geschichte von denen geschrieben, die uns das unsere weggenommen haben, unser Land, unser Denken. Jetzt haben wir im Rahmen unserer Verfassung die Möglichkeit, unsere Geschichte selbst zu schreiben, wir sind Protagonisten. Wir schreiben sie gerade, wir schreiten vorwärts an der Seite des Comandante Chávez. Wir denken nicht wie der Comandante Chávez. Es ist der Comandante Chávez, der denkt wie wir. Deswegen ist er dort und deswegen werden wir dafür sorgen, dass er dort bleibt.

Juana Ruíz, Verantwortliche für Verkauf

Wenn das Volk wirklich glaubt, es kann den Sozialismus machen, dann wird es den Sozialismus machen. Wenn das Volk aber nicht glaubt, dass der Sozialismus möglich ist, dann wird es keinen Sozialismus geben, auch wenn 10.000 Chávez kommen.

Papierfabrik Invepal, Morón (Carabobo)

Manrique Gonzales, Produktionskoordinator, Angestellter des Staatsanteils

Im Jahr 2003 sahen die Arbeiter von Ex-Venepal, dass die Schließung ihres Betriebs bevorstand.

Die Arbeiter begannen also sich zu organisieren und zu kämpfen. Sie schlagen der Regierung die Möglichkeit vor, ohne die Unternehmensleitung Eigentümer oder Teilhaber des ehemaligen Unternehmens Venepal zu werden. Es beginnt der gesamte Prozess von Versammlungen und Demonstrationen. Das Arbeitsministerium unterstützt sie schließlich, damit sie sich in einer Kooperative organisieren. Denn sie mussten eine legale Grundlage bekommen für den Kredit, den sie für die Rettung des Unternehmens forderten. Das war 2004, als die Unternehmensleitung endgültig zurücktritt und die Regierung die ja vorher schon einiges gemacht hatte beginnt, den Prozess zu beschleunigen. Ich arbeite mit Leuten der Regierung und wir haben das Projekt zur Rettung ausgearbeitet. Ende Februar, Anfang März, wurde ein Vorprojekt eingereicht. Die Autoritäten der bolivarianischen Regierung analysierten es und genehmigten 7,5 Millionen Dollar. Als wir das Geld bekamen und von der Staatsanwaltschaft die Genehmigung zur Nutzung der Invepal-Anlagen hatten, haben wir die Rohstoffe geordert und am 14. Mai 2005 mit der Produktion begonnen, das war die Maschine 2. Wir hatten gleich eine gute Leistung und haben mit der Wartung der Maschine 3 weiter gemacht, die für Kopier- und Schreibpapier, die dann am 16. August anlief.

Invepal, bekam den Kredit zu sehr niedrigen Zinsen, vier Prozent und mit 20 Jahren Rückzahlungsfrist.

Aktuell gehört das Unternehmen zu 51 Prozent der Regierung und 49 Prozent den Arbeitern, die in der Kooperative COVIMPA organisiert sind. Aber wenn nach und nach der Kredit abbezahlt wird, übergibt die Regierung ihre Anteile, bis die Arbeiter Besitzer von 99 Prozent der Aktien sind und die Regierung behält eine sozusagen goldene Aktie.

Bei dem Rhythmus, den Invepal jetzt hat und wenn die kleinen Unwegmäßigkeiten korrigiert werden, die vorkommen, wenn ein Unternehmen gerade mal drei Monate läuft, denke ich, Invepal wird die Schulden vor der vereinbarten Zeit zurückzahlen.

Wir haben einen ganz guten Rhythmus. Nächstes Jahr werden wir die Zahlungen etwas beschleunigen können und einen Teil des Geldes für soziale Aufgaben verwenden und für die Erneuerung der Technologie. Denn die vorherigen Eigentümer hatten hier seit 1992 nichts mehr investiert.

Rowan Jiménez, Wartung, Kooperative Covimpa

Nach drei Jahren Kampf, den wir Arbeiter hier in Morón im Bundesstaat Carabobo in Ex-Venepal, heute Invepal, geführt haben, konnten wir das Unternehmen wieder zurück gewinnen.

Wir waren das erste Unternehmen, das enteignet wurde.

Die Regierung hat uns die Möglichkeit gegeben selbst zu entscheiden, wer der Fabrikdirektor ist, und wir haben beschlossen, es soll der Generalsekretär der Gewerkschaft sein, der Freund Edgar Peña, um so die gesamte Kontrolle über das Unternehmen zu haben.

Willys Lugo, Laborarbeiter, Kooperative Covimpa

Durch den Kampf wurden wir alle geeint.

Persönlich habe ich gelernt, wie soll ich das sagen, mehr Mensch zu sein, weißt du? Ja, ich sage das ganz ehrlich, mehr Mensch zu sein. Manchmal irren wir uns... Damals, wenn du einen Posten hattest, also ich war Angestellter, dann hast du die anderen als untergeordnet angesehen. Das sollte nicht so sein. Jetzt ist es nicht mehr so, jetzt sehen wir uns alle als gleich an. Aber damals, in der Zeit des Kapitalismus, wie wir immer sagen, da haben sie uns diese Ansichten eingeflößt, so dass wir auch Teil dieser Kette waren. Also haben wir den anderen als uns untergeordnet angesehen, weil wir Angestellte waren, weil wir das und das waren: Aber jetzt nicht mehr, wir sehen uns alle als gleich an und teilen alles, was wir haben.

So sind wir auch solidarisch mit anderen Leuten. Wir haben z. B., als wir mit der Produktion von Heften begannen, diversen Schulen Hefte geschenkt.

Wir haben auch die Schule hier wieder eröffnet, denn vorher musste hier für die Schule bezahlt werden. Jetzt nicht mehr, jetzt gibt es eine bolivarianische Schule und jeder, der sich einschreiben will, schreibt sich ein und studiert. Auch die ärztliche Behandlung nutzten vorher nur wir Arbeiter, aber nicht die Gemeinde. Jetzt kann auch die Gemeinde herkommen.

Rowan Jiménez, Wartung, Kooperative Covimpa

Aktuell hat eine Gruppe Arbeiter hier im Bundesstaat Carabobo beschlossen, eine Fabrik in Valencia zu übernehmen, die Oxidor heißt. Wir als Arbeiter von Invepal geben ihnen alle Unterstützung, die wir leisten können. Das sind konkret Lebensmittel, Geld und die Produkte, die wir selbst produzieren, wie etwa die Hefte. Denn wir wissen, dass die Situation, die sie durchmachen, die gleiche ist, die wir Arbeiter alle durchgemacht haben, als wir unser Unternehmen besetzt haben. Wir denken, es ist der Moment, dass alle Beschäftigten, die Abeiterklasse und auch die Studierenden, die Menschen unterstützen müssen, die Besetzungen beschließen, um ein Unternehmen zurück zu gewinnen. Denn mit der Rückeroberung von Unternehmen werden auch Arbeitsplätze geschaffen. Ein Beispiel, das uns mit Stolz erfüllt, ist unser Fall. Wir waren zuletzt noch 300 Beschäftigte, heute sind wir 630. Das heißt, wir haben 330 Arbeitsplätze geschaffen. Wir wollen, dass alle, auf nationaler und internationaler Ebene, sich bewusst werden, dass, wenn die Arbeiter ein Unternehmen zurückgewinnen, das nicht für sie alleine ist, sondern um mehr Arbeitsplätze zu schaffen und den Gemeinden zu helfen.

Das Werk ist ja erst vor sechs Monaten wieder angelaufen. Aber wir haben unsere Arbeit im sozialen Bereich geleistet, denn das ist das Wichtigste. Wir müssen zu verstehen geben, dass wir nicht ein Unternehmen zurückerobern, um dann wieder Kapitalisten zu sein. Wir müssen die Unternehmen zurückerobern, um Sozialisten zu sein, um auf das Soziale zu zielen. Denn sonst glaube ich, dass es in gewisser Weise die Mühe nicht Wert ist, dass die Basis, die Leute, die Gemeinden, sich dem Kampf der Arbeiter anschließen, wenn diese sie morgen wieder im Stich lassen.

Als Kooperativenangehörige in Invepal werden wir das nicht vergessen und nicht später Leute einstellen und sie ausbeuten.

Es muss auch unterstrichen werden, dass wir mit diesem Kampf auch die Bildungsmissionen in das Werk geholt haben, wie etwa die Mission Ribas, die Mission Sucre und die Mission Robinson. Das ist sehr wichtig, da die ehemaligen Besitzer die Missionen nicht zuließen. Jetzt gibt es sie und in diesem Monat ist das Universitätsangleichungsjahr (PIU) der Mission Sucre zu Ende. Hier in Invepal haben es etwa 100 Arbeiter geschafft und beginnen jetzt ein Universitätsstudium.

Ich denke, damit die Mitverwaltung gestärkt wird, muss es eine sozio-politische Schulung eines jeden Arbeiters geben, damit wir exakt wissen, in welche Richtung wir gehen. Wir können uns nicht nur auf die Produktion konzentrieren. Nein, wir müssen auch in die Verwaltungsbereiche gelangen. Wir müssen uns bilden, um die vollständige Kontrolle des Unternehmens zu erreichen.

Manrique Gonzales, Produktionskoordinator, Angestellter des Staatsanteils

Dieses Unternehmen gehört mehrheitlich dem Staat. Aber wir sind keine Funktionäre. Das hat einen Grund, denn wenn wir staatliche Funktionäre wären, dann würden wir in Venezuela beginnen, Staatskapitalismus zu machen. Das ist, wie wir wissen, schon in Russland gescheitert. Wenn der Staat anfängt, sich in Unternehmen reinzuhängen, die von den Arbeitern verwaltet werden, und Entscheidungen trifft, die der Regierung folgen, dann ist das, als ob der Staat sich alles aneignen würde, und das ist nicht die Idee.

Eleuterio Córdova, Gruppenkoordinator Papiermaschine 3, Kooperative Covimpa

Alle Ämter hier wurden von der Versammlung gewählt und für alles, was im Unternehmen läuft, muss die Versammlung berücksichtigt werden. Die Einkommen sind alle gleich... Wir haben das gleiche Einkommen. Die Leute, die anfangen im Unternehmen zu arbeiten, werden in der Versammlung gewählt. Hier haben wir alle großen Respekt vor der Versammlung. Entscheidungen, die getroffen werden, müssen in der Versammlung abgestimmt werden. Bis die Versammlung nicht zustimmt, wird hier nichts ausgeführt.

Rowan Jiménez, Wartung, Kooperative Covimpa

Ich denke, um unseren Prozess in Richtung Sozialismus weiter zu stärken, müssen wir vor allem alles komplett überdenken: Die Arbeiter, das Volk und auch die Leute, die in der Regierung arbeiten. Wir müssen ehrlich sein und in Richtung Sozialismus arbeiten. Nicht, dass wir nur eine Gruppe sind, die wirklich reinhaut für den Sozialismus, sondern dass auch die Leute, die mit der Regierung zu tun haben, das gleiche tun, offen partizipieren, dem Volk Partizipation geben, dass das Volk auch in diese Richtung geht, dass die Leute nicht warten, dass sie ihnen immer alles geben, sondern, dass sie sich organisieren.

Wenn wir nicht partizipieren, wenn wir nicht Bewegungen organisieren, wie es sein muss, dann wird der Sozialismus in Wirklichkeit nur auf bloße Worte beschränkt bleiben.

Alcasa Leitungssitzung

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Das ist eine Versammlung von einigen Teams, die in der zweiten Phase der Mitverwaltung an einer pädagogischen Kampagne arbeiten, in der es um den partizipativen Haushalt geht, um technologische Anpassungen, Restrukturierung des Unternehmens; ein Wechsel nicht nur im Organigramm, in der Arbeitsweise und in der Unternehmensstruktur, sondern in den Normen und Regeln

Luis Mata Castillo, Universitätsprofessor

Das Konzept, das Ziel, ist: den Prozess der Mitverwaltung vertiefen mittels einer partizipativen und protagonistischen Methodologie in der Entscheidungsfindung, Kontrolle und Ausführung der Pläne. Ein Projekt, das Alcasa in ein soziales produktives Unternehmen unter der selbstverwalteten Kontrolle der Arbeiter und ihrer Gemeinden verwandelt.

Carlos Lanz, Präsident von Alcasa

Wir haben hier folgendes Problem: Wer in einem bestimmten Bereich der Kohleabeilung arbeitet, kennt nicht die Gesamtheit der Kohleabteilung, er kennt nicht die Gesamtheit der Beziehung zu anderen Abteilungen, und noch viel weniger das Verhältnis des Aluminiums mit dem produktiven Sektor. Die technologische Diskussion über die organisatorische Neuordnung muss dazu führen, dass der Alcasianer eine Gesamtvision hat, integral, für die gesamte Fabrik, das Werk

Das ist ein spezifisches Ziel

Ja, aber in diesem Fall ein politisch-ideologisches. Das heißt, die Herrschaft spiegelt sich in der Atomisierung des Wissens wieder, in der Parzellierung des Wissens. Wenn du einen Arbeiter, der auf eine bestimmte Sache spezialisiert ist, da heraus nimmst, dann kooperiert er nicht mit den anderen aufgrund seiner fragmentierten Sichtweise. Also müssen wir den Prozess rekonstruieren, indem wir die Fäden sichtbar machen.

Ein weiteres Element ist der Widerstand gegen Veränderung. Wir haben Probleme mit ablenkenden oder dissonanten Praktiken einiger Leute; aus Angst vor dem Unbekannten, durch das Verlieren des Interesses... und es gibt bewussten Widerstand. Wir haben Bereiche des Widerstands gegen Veränderung im gesamten Werk, in einigen Sektoren mehr, in anderen weniger. Und wir müssen eine Strategie haben, die auf diese Problematik ausgerichtet ist, inklusive Einzelfallstudien oder indem wir eine Art Bestandsaufnahme machen, eine Karte der Konflikte, die auf der Grundlage des Widerstands entstehen.

Die Verwurzelung, das Zugehörigkeitsgefühl, hat mit Ethiken und Werten zu tun, aber auch mit einer Wende im Alltag des Arbeiters bezüglich seiner Identifikation mit dem Arbeitsplatz. Diese ist aber nicht Taylorismus, nicht Fordismus und auch nicht Neofordismus, es ist etwas anderes, im Sinne der Humanisierung des Arbeitsplatzes... diese hat mit Umwelt und Gesundheit zu tun, mit den Arbeitsbedingungen... Denn wir dürfen nicht die Ausbeutung der Arbeit steigern, was die Grundlage der kapitalistischen Rentabilität und Produktivität ist, die auf der Ausbeutung beruhen.

Wie richtet sich ein Unternehmen, das ein kapitalistisches Regime hat, nicht nach der Ausbeutung der Arbeit oder dem Gewinn? Das ist ein Widerspruch, ein Paradox, auch für die Arbeiter selbst. Das Problem der Anreize erinnert euch daran, dass wir das Problem haben, wie wir die Arbeit entlohnen, Verringerung der Arbeitszeit, automatische Lohnanpassung, Arbeiterkontrolle, also die Losungen, die wir eingebracht haben, beginnen zu kreisen. Wäre es nicht möglich, den Arbeitstag zu verringern und noch eine Schicht einzuführen? Das ist eine Idee, an der wir arbeiten, um die Arbeit zu humanisieren. Aber da gibt es Leute, die sagen, das sei nicht produktiv. Denn die Logik hier ist, dass Personal reduziert werden soll, dass wir zu viele Arbeiter haben. Das ist der traditionelle Ratschlag, also sollen wir wie im Stahlwerk Sidor die Hälfte rauswerfen. Das ist das Beispiel, dass sie uns mit Sidor geben. Sidor hat eine gute Arbeitermitbestimmung, weil die Gewinne aufgeteilt werden und weil 9.000 Beschäftigte auf die Straße gesetzt wurden.

Hugo Favero, Wartungsingenieur

Ja wirklich, welches ist das Nutzenkriterium: die Arbeiter rauswerfen oder Gewinn machen...

Luis Alfonso, Ingenieur, Finanzverwaltung und politische Analyse

das führt dazu, eine neue politische Kultur im Unternehmen zu sozialisieren, in der sich der Beschäftigte in alles einmischt, was mit dem Unternehmen zu tun hat. Das war vorher nicht so. Der Arbeiter wurde in eine Schublade gesteckt und war nicht Teil der Entscheidungsfindung die Information, dass die Finanzen offen gelegt werden, und auch eine neue Art der Leitung, eine partizipative Unternehmensleitung

Luis Mata Castillo, Universitätsprofessor

So sind wir, wir zeigen etwas auf, wir beginnen zu überlegen und bringen eine neue Idee hervor, die den Prozess weiter perfektioniert. So ist die Dynamik des Transformationsprozesses. Der Prozess der Veränderung ist nicht steif.

Elio Sayago, Umwelttechniker

Genau aus dem Blickwinkel der Mitverwaltung ist es wichtig, dass die Sprecher, die Arbeitstische, die Leitungstriumvirate oder die Geschäftsführung, die letztlich bleiben wird, ein Minimum an Normen haben, welche die Verhaltensweisen in allen Bereichen vereinheitlichten. Wir müssen alles reglementieren, was mit Sprechern, Komitees und Geschäftsführungen zu tun hat. Es gibt einen Vorschlag, aber er muss genau von den Beschäftigten in Ausübung der Mitbestimmung angenommen werden. Wenn wir als Kampffeld die Projekte technologischer Anpassung nutzen, wenn wir alle Vorgehensweisen evaluieren, alle Schritte, ab dem Moment, in dem die Notwendigkeit des Projektes aufkommt, bis zu der Ausführung, sind da eine Reihe bürokratischer Schritte, die der Beschäftigte anfangen muss zu kontrollieren. Das wird von den Arbeitern, die mit der wirklichen Notwendigkeit des Verfahrens zu tun haben, kontrolliert, definiert und genehmigt werden müssen. Was wird gekauft? Wo wird es gekauft? All das hat früher eine Person gemacht, jetzt muss es das Team machen, das aus dem Bereich der Kenner der Materie kommt.

Carlos Lanz, Präsident Alcasa

Die sozialistische Erfahrung oder der so genannte sozialistische, realsozialistische, dieser bürokratisierte sowjetische Sozialismus... Der Staatskapitalismus war nie Sozialismus Er hat uns gelehrt, dass die Veränderungen in den Produktionsverhältnissen... In Alcasa haben wir deutlich gemacht, dass der Beginn der Veränderung der Produktionsverhältnisse nicht nur auf das Eigentum zurückzuführen ist. Denn was sie in der Sowjetunion gemacht haben, war verstaatlichen und nationalisieren. Aber die Geschäftsführung ging nicht in die Hände der Arbeiter über. Seit 25 Jahren schon behaupte ich, dass die Revolution nicht möglich ist, wenn wir nicht die Diktion der Arbeit verändern. Es ist ein vergessenes Verhältnis, naturalisiert, etc.

Wir haben uns hier also dazu entschlossen, und da nehmen wir den Präsidenten der Republik beim Wort, der gerade Beyond Capital (Jenseits des Kapitals) von István Mészáros liest. Wir haben Seminare mit diesem Autor organisiert und eine Reihe Sachen festgestellt, die uns dazu führen, die Debatte um Technologie und Wissenschaft zu vertiefen. Denn hier wird ein Kult um Technologie und Wissenschaft betrieben. Wenn wir von Entwicklung reden, davon, Maschinen zu kaufen, die unseren Umständen angepasst sind, dann müssen wir eine Debatte darüber führen, von was wir reden. Von Produktivität. Welche Produktivität? Wettbewerbsfähigkeit. Welche Wettbewerbsfähigkeit? Qualität. Welche Qualität? Das sind keine neutralen Werte. Das ist axiomatisch und ideologisch aufgeladen. Daher haben wir beschlossen diese Richtung zu vertiefen. Z. B. das Verhältnis, das zwischen Wissenschaft und Technologie besteht und dem Verhalten der Gewinnspanne. Warum wird im Kapitalismus die wissenschaftlich-technische Entwicklung nicht zu Gunsten der Mehrheiten eingesetzt? Warum wird eine technologische Innovation nicht permanent integriert, um mehr und im Überfluss für alle zu produzieren? Warum besteht sogar eine Irrationalität der Ökonomie, wenn die Wissenschaft und Technologie nicht im Dienste des menschlichen Wohlergehens genutzt wird? Warum definiert die Oszillation der Gewinnspanne die technologische Innovation der Unternehmen?

Das schlimmste hier ist der intellektuelle Kolonialismus unserer Arbeiter. Sie folgen der Mode, sie pflegen einen Kult um die Spitzentechnologie, ohne zu wissen, von was wirklich die Rede ist, ohne die komplexen Implikationen zu kennen, die das Problem der Wissenschaft und Technik mit sich bringt. Wir werden also ein Dossier veröffentlichen, das alle Sichtweisen darstellt und so die Debatte erleichtert. Das muss entmythifiziert werden. Denn die Wissenschaft und Technologie haben eine Macht. Sie sind wie eine Art Religion. Ich habe heute mit Public Relations gesprochen, um das Material massiv zu vervielfältigen, damit wir uns mit einer Artillerie des Denkens bewaffnen, um das zu vertiefen, nicht die Angelegenheit mit traditionellen Diskursen über Wissenschaft und Technik zu vereinfachen, sondern komplex. Wir müssen wissen, dass wir Maschinen kaufen, Modernisierungen vornehmen, aber nur, wenn sie sich in einem alternativen, andersartigen Paradigma bewegen. Daher gibt es eine Revolution in diesem Prozess und daher ist unsere Mitverwaltung anders, als Aktien unter den Arbeitern zu verteilen oder sie auf einen Sessel des Vorstandes zu setzen, was die sozialdemokratische Orientierung der Mitverwaltung war. Wir reden über eine revolutionäre Mitverwaltung, eine Veränderung der Produktionsverhältnisse.

Dialogliste Englisch

A film by Dario Azzellini & Oliver Ressler

Alcasa, Guayana City (Bolívar)

Carlos Lanz, President of Alcasa

Were at Alcasa Company, a company under the umbrella of the Corporación Venezolana de Guayana (CVG), which assumes responsibility for regional development as a company, as a holding company of a group of sixteen companies. This aluminum company is called CVG Alcasa, which is formally assigned to the Ministry of Basic and Mining Industry (MIBAM).

We are 2,700 workers here at Alcasa.

Elio Sayago, Environmental Technician, Board of Directors

In December of 2004, the President of the Republic requested a project from each company of the CVG to see the viability of co-management within the State companies. Fortunately in January (2005) there were changes in the Ministry, in all of the CVG. The Ministry of Basic and Mining Companies was created. Mr. Alvarez was named Minister, Carlos Lanz was named President of the Company and a Board of Directors was named, for which I was selected as part of the CVG, because I was a worker, to join the Board of Directors.

In fact, the work of co-management that began to be applied at Alcasa broke with historically established schemes, with respect to co-management up until now. Historically it was referred to as German, Soviet, Cuban co-management, which for us was always centered around elements of class collaboration, guided by social democracy, with respect to giving workers a bit of stock and to sharing company management.

Exactly what were doing here at Alcasa doesnt have anything to do with that. We started a co-management scheme but based on production relationships. Of course, thats why co-management for us is a transitory process to a controlled process by the workers, or self-management.

Carlos Lanz, President of Alcasa

The new organizational culture, the political culture of Alcasa, is not only values, general ideas, but also becomes visible in organizational models, in democratic procedures. Since we arrived here we have argued for a change in management structures, and new managers were elected with the idea of making joint decisions and of working as teams. Thats why a trio was elected, three managers instead of one, transitional, revocable, subject to the workers control. But its not all based on the election of managers; we also elect 300 spokespeople, which is a link between the workers assembly, the work committee and management. So these 300 spokespeople are by definition, as the name implies, the ones who manage the proposals, consult, research, and together with the collective, decide the policies to implement, of any kind: environmental, technological, claims, and cultural.

Thanks to our Constitution we have a gateway to a different democratic socialism, with worker democracy, where there are elections. Actions are accounted for, jobs are revoked and delegated, and we have another paradigm of a participatory and protagonistic democracy.

Leslie Turnero, Lamination Management Trio

Within the co-management processes that are going on at CVG Alcasa, we were the first trio formed on March 23 this year, and we were elected from 260 workers.

After the elections, the first thing we did when we were formed as a trio was to make a call to the whole worker mass for them to participate with us to diagnose the whole plants situation and for the workers to become directly involved in reaching the solution to all the problems that we had, since then management works with open doors, as we call it, where all workers are co-participants in decisions.

What we have noticed when we speak with other companies, that when the president goes with us and says, Dont speak directly to me, speak to the new managers, it is a very big shock for people because all the changes bring a huge reaction. There has always been a pyramid structure with only one person leading.

So the ones who doubted about even our slightest resultsfrankly in our four months of production weve made four production records and records indicators in our management goalsnow they say, We dont see it as such a bad thing.

Gonzalo Maestre, Supervisor and Spokesperson, Rodding Department III

At least in the work environment were improving a lot. Weve now reduced the use of a material called chlorine. Very little chlorine is being used. Were using furnaces with better technology. Other equipment is going to be bought, like cooling towers, in order to improve our production. We are going to put in new melting furnaces for greater mechanization. They are more modern so we can compete in the market. Thats what we will be improving in this area. We are improving the education of the workers, were mechanizing. Whoever wants to get a high school diploma, an engineering degree, or get an advanced technical degree or whatever, were there getting a consensus from the workers for that kind of improvement.

Carlos Lanz, President of Alcasa

This is a democratic process designed to break the backbone of the hierarchical structure of boss, foremen and workers.

The bottom line is that here we are building a new political culture. We are making reality making the Constitution concrete through worker participation. We are doing so, with obsolete technology, environmental disregard, organizational problems, bureaucratic problems, but the political dimension dominates, that is our proposal for Alcasa.

I was appointed director of the CVG, which is the holding company, by the president of the Republic. I was designated president of the company to encourage co-management. My task here is endogenous development, co-management. But I wasnt elected by the workers because this is a co-managed company, where one part had been legitimized institutionally as the new management, but I am with the State, and I represent the State. On the way to self-management we have to allow the workers to elect the board of directors as well. That is a process, which now comes as part of the development of co-management. Co-management involves co-responsibility, co-participation. I even have the prerogative as manager to name directors, to name all the trios, but to be democratic we have turned down this legal prerogative in order to allow the development of worker democracy.

And in a way, I am not a president, a traditional manager. I am a revolutionary lent to this company for political and ideological reasons. In fact, I have even said that I dont know about aluminum, although by now I have had to learn a lot about aluminum. My role here is political and ideologicalto work as a political and educative director more than a technocratic one.

Marivit Lopez, Endogenous Development Unit

Alcasa is a state-owned company and up until now has exported 80% of its production. We are pushing for the endogenous development of the nation and, as such, we intend to reverse that situation. And in order to do that we have to support companies, industries that transform the aluminum in our country, specifically in the most excluded zones of the region.

Carlos Lanz, President of Alcasa

That development model is comprised of social subjects and has a perspective that we call a transition towards socialism of the 21st century. Alcasa is advocating for a set of new companies, which we call in Venezuela social production companies (Empresas de producción social, EPS), which are not geared to profit, to earning, rather to social equity, to justice, to the integration of the population, of the citizens.

Marivit Lopez, Endogenous Development Unit

In addition, theres the part of training of course, in order to understand that they are not going to be new capitalists, rather they are companies where the surplus is the most important thing. The surplus must be distributed in the community in which they are operating. So Alcasa is also lending them, lets say, assistance so that those projects may crystallize, helping them in anything related to political and technical training.

A specific case of social production companies, which are moving ahead, going along with Alcasa, are Furepirupa and Alumifenix. They are companies, which give added value to aluminum. In the case of Furepirupa, it is a foundation, which now is going to be converted into a network of cooperatives. They are making urban transport units.

José Luis Acosta, Furepirupa Minibus Cooperative

As a project, Alcasa is supporting us with the material, and the communities organized by cooperatives, totaling twelve cooperatives, are joined to this project within the endogenous nucleus. This prototype will lead to developmental improvements in Guayana City transportation, with the cost of, and its important to highlight this, 40% less than what the current market cost is of a normal van.

Carlos Lanz, President of Alcasa

Historically, there have been unemployed people at the gates here, unemployed people that are grouped by unions that have been struggling against us for a long time. We have been battling with them. And so we are creating a training center.

This is a group of construction workers that is very violent. They are people who are excluded, people who belong to sectors that we have favored in our work with them. So they work by season, on projects and every time they finish projects they become unemployed again. So we want to include them in a technical process of productive and socio-political training, create a space where they can meet and avoid confrontation, because it is a group that has had many confrontations. There have been deaths, shootings, and attacks with weapons. They are groups that have been surrounded by mafia. There are many groups, but the one that is with us has integrated itself to work in the plant. And then part of the EPS is to somehow integrate them permanently in the work. Were going to set the first stone because it is a historical event that the company is taking care of the unemployed in another way, economically, socially and culturally integrating them.

Some say that what Im doing is pure rhetoric, ideology, politics. You can see that Im being attacked for that, and I defend the idea that without pedagogical action, education, brothers, we wouldnt have gotten where we are.

We have to push for a new workers movement, different from the corrupt movements of the usual unions, that simply negotiate contracts, negotiate jobs. The union bureaucracy, brothers, has to be attacked too, in the same way we attack the empire, we attack the transnationals. We have to fight for union democracy.

A class-based revolutionary workers current must be constructed here. And this is also a center aimed at worker training. That is our goal, our task, as winners, I invite you to join in that great liberating effort.

Elio Sayago, Environmental Technician, Board of Directors

What we need right now is that our union leaders, and the other comrades understand that right the leadership must aim for the workers to take a leading role. How to make sure that the workers knowledge really guarantees control. How we, as union leaders, are able to get the knowledge and wisdom of our people, in these moments, to go beyond the traditional union claims. And we in these moments have the historical opportunity to construct society, to define our own destiny.

Marivit Lopez, Endogenous Development Unit

The problems that we have had at Alcasa with the implementation of co-management have to do with a training process. We werent prepared to have the control of the company. Even so, I think we have made great steps forward; maybe we have to strengthen teamwork. We have begun to form work committees with participants from different areas. But they have slumped a bit because they havent had a clear direction. Where there have been well-trained people, and people who were clear about the process, things have advanced. But in those parts where workers dont have good political training or a clear idea of what we wanted, work has dropped a little bit. Nevertheless, we are currently encouraging the work of committees again, and we are channeling all the concerns in order to give these committees a direction on the basis of three points. One, a participative budget; two, the technological upgrading that the plant needs in order to continue functioning; three, socio-political training, because of course in order to take control the people must be trained and understand the reasons why we are doing things.

Carlos Lanz, President of Alcasa

But its a fact that this is still capitalism, and how does a company push toward socialism within a capitalist framework? That is the challenge of the Venezuelan revolution. If we see it as a transition where the old hasnt died and the new hasnt been born, we have to push the new production relationships, strengthen them, and assist them.

But there must be global changes. I dont think that there can be a micro-change if we dont transform all the structures of the Venezuelan State, the Venezuelan society. But we are readying the ground. We cant expect to change everything in order to begin to change. Here we are clear about the dialectics between reform and revolution.

And if the direction of the Bolivarian Revolution is towards socialism, we are one of the companies or pioneer projects which is changing the production relationships without them having changed globally. And the attack on the social division of work is a civilizing change. No other revolution had proposed this openly.

Elio Sayago, Environmental Technician, Board of Directors

President Chávez recently made a reference that this was a historical opportunity after five hundred years, after two hundred years. And what is going to be the guarantee that we dont make a mistake? Or that it doesnt happen to us again that we go through some kind of transitory well-being and then the exploitation of people by people returns. For us it has to do exactly with the dimension of consciousness, of knowledge. We differentiate information that regularly moves a society and human knowledge, from what is really being done. Were always saying that we should remember that under the intellectual authority of Aristotle, humanity spent a thousand years believing that the earth was flat. Imagine, a thousand years of potential for the development of the human being under that concept. Were talking about something of that magnitude. Were talking about the fact that traditional concepts, including class struggle, have to be adapted for what we are going to build. Theres a typical argument going on right now, within the revolutionaries, whether we face and destroy the enemy or what do we have to do. We prefer construction rather than destruction. When we build we are guaranteeing destruction. And if we concentrate our workers, our people, on the construction of new human relations, which is for us what is at stake, we are guaranteeing the destruction of the established. The destruction of the blocking, up until now, of the potential for human growth.

Textile Workers Cooperative of the Táchira, San Cristóbal (Táchira)

Dulfo Guerrero, Coordinator of Plant I

This was a company that produced practically at 99% level. A company, that sold a lot. It was a company that wasnt closed for economic reasons, for the way it functioned, or for lack of raw material or anything, but for negligence on the part of the bosses who were at that moment at the head of those responsibilities. They didnt care about the company as such rather they simply used it as a guarantee in order to get loans. But the company never got any of that money. And then the moment came when the companys debt was a much greater amount, unpayable. They closed it in the most irresponsible way, even kicking us out without giving us what we were legally entitled to.

José del Carmen Tapias, Education and Social Development Coordinator

Textileros del Táchira is one of the 75 Venezuelan companies rescued by workers. After almost four years of being closed, the ex-workers of this company organized themselves as a cooperative. Undoubtedly one of the great supports we got was from the strength transmitted to us by our president Hugo Chávez Frías, when he said Organize yourselves as cooperatives. The rescue of the closed companies took place in different ways, but always with the active participation of the worker. We have self-managed cooperatives, in our case, Textileros del Táchira, which the workers rescued directly without participation from the business owner or from the government. We have credit from the government, which must be paid, but we are a cooperative, which is managed, led and directed by the workers, by its legitimate owners.

We are sowing cotton at this time, so that the Táchira will give us cotton and we will be able to cover that demand. But also to open up job opportunities in the agriculture sectors in order to get it involved in the sowing of cotton. We have suffered and we are the victims of capitalist sectors that drive the prices of cotton as they wish. Because of this we are interested in the producers and negotiate cotton directly with them; we want to cut away from the capitalist sectors, which have always driven the economy of the country.

Luis Alvarez, Administrative Director

To move this project ahead, to create this cooperative, we got a work team together made up of engineers and administrators for which we drew up a work plan, a project, which was presented to the national entities on the 19th of March, 2005. After a year and a half of difficult struggles, trips to Caracas, important meetings, we were able to sign a grant for a 3.4 billion Bolívars credit.

After obtaining the credit we launched a phase of 40% production. Currently we are processing 40,000 kilos of cotton, all of domestic production, in order to enter little by little into the market and make a call out to more people. At the moment we have 118 people but to reach 100% capacity we should have 226 people working in this cooperative.

We have a one-year grace period with quarterly payments for a total of 176 million Bolívars over an eight-year period. Our goal, as projected with our cash flow, is that in a maximum of four years this credit will be paid because it should be self-supporting, to pay off this loan.

By means of this cooperative model, what we are looking for is not to enrich the peopleeven less that they would make less and be exploitedbut rather, what we are trying to achieve is that we should have a better quality of life, that our members should have decent housing, that our children should have a decent education. Using this model we hope to arrive at what we call or what the president calls: socialism of the 21st century.

Rigoberto López, Loom Department Coordinator

Hierarchies dont exist, were all equal. We depend on an assembly, which governs the cooperative in any moment of doubtanythingwell go to the assembly to discuss things. They approve or dont approve. The assembly is basically governing the company. For example, theres the presidency, theres auditing, finance, but those are administrative positions.

When we had the idea for the cooperative, when they asked me if I wanted to be part of the cooperative that was going to open, that was in the project phase, for me it was a great joy, because all my life Ive been a textile worker. Ive been a textile worker for almost 43 years. This was after being out of work for four and a half years, when I didnt have anything to do, because I was there trying to operate a small business and it didnt work. For me it was a big deal because to do what Ive done all my life, to continue in the samemechanics, management, all the things that one manages within a departmentthats important for a person, to recuperate life again practically.

Carolina Chacón, Administration

I started out at Telares del Táchira in 1995 and thats where I was until the company closed. Since I worked for these five years, I cant complain. It went well for me, but the decisions that one made or the ideas that one could give were not taken into account. Only what the boss said. And they would have closed meetings from which no information ever came out to the worker, employee or laborer. We simply had to limit ourselves to a few roles. Eight to twelve and two to six, for example, then go home and we could never give any ideas. When the company closedI basically was born in this company because my mother worked here since 1976it was very unfortunate for us because our whole life was here in Telares del Táchir.

One day the idea came up to start a cooperative. For us it was surprising or really a dream that you couldnt quite feel yet. Afterwards, we saw that through the government, we could make this dream come true. The social dimension is very important in the work of cooperativism. That is what interested us most, especially me.